A drop test gone very wrong

Since 2014 I have done 100’s of drop tests and most of these have taught me something new about the ropes and equipment we use as technicians.

I have shared results and discussed testing methodologies with many people and have always spoken loudly of the hazards with stored energy in the system and what these present to people.

However, on 8th October 2020 I was hit hard in the face by a steel chain during a test. In the week since, while recovering, I have tried to work out how this happened and how I could have been such an idiot.

In this article I will share the details in the hope that I and others may learn.

Please don’t read this thinking things like “that would never happen to me because I…”. Things happen to us most days. For those that test and break equipment, how many times have you not been able to find that small piece of carabiner that flew off? How many times have you dropped something while working at height and it has not hit anyone? I have often said that there are two kinds of people who work at height: those who drop things, and liars.

Read this report with humility and the realisation that all of those amazing qualities it takes to be human also, at times, leave us as exactly that – very human and, just like all other humans, prone to making mistakes.

The test

I was planning on testing the reduction in strength caused by choking Dyneema slings. I could do this on the bench with a slow-pull test but I have seen more and more technicians using these for anchors at work. This means they could see 6kN as a dynamic force in the event of a mainline failure when caught by a backup system. If used as an overhead redirection anchoring a pulley, then this could be as high as 12kN.

These slings normally have a stated MBS of 22kN when brand new and used end-to-end.

Traditional theory says choking reduces the strength to something between 50% and 80% of the MBS. So, at 80% maintained strength, a 22kN choked sling reduced to 17.6kN sounds OK-ish. However, at 50% this goes down to 11kN – which is now less than 12kN mentioned above.

Where do the skinny 8-10mm Dyneema slings many of us use fit along this 50-80% scale? Dyneema has a much lower melting point than many other sling materials so suspect closer to 50 but I wanted to do the tests.

The setup

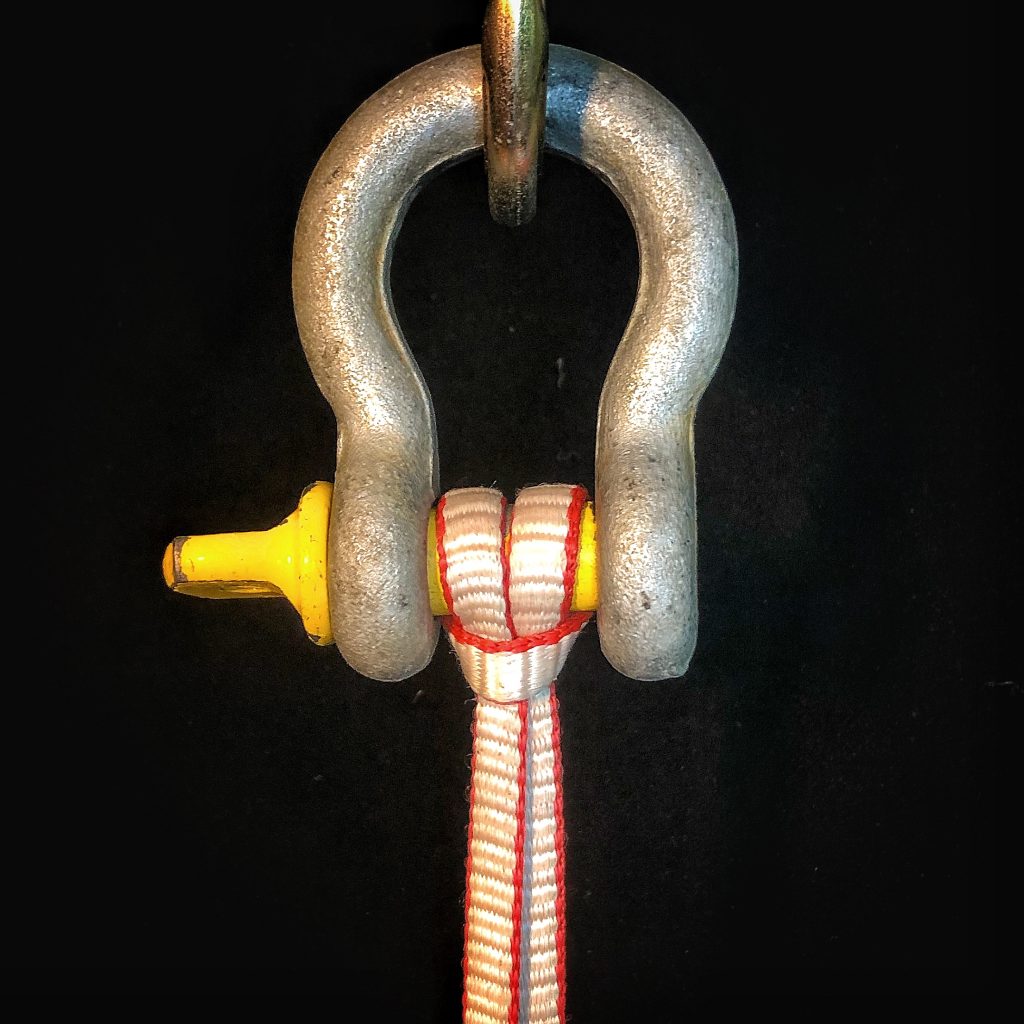

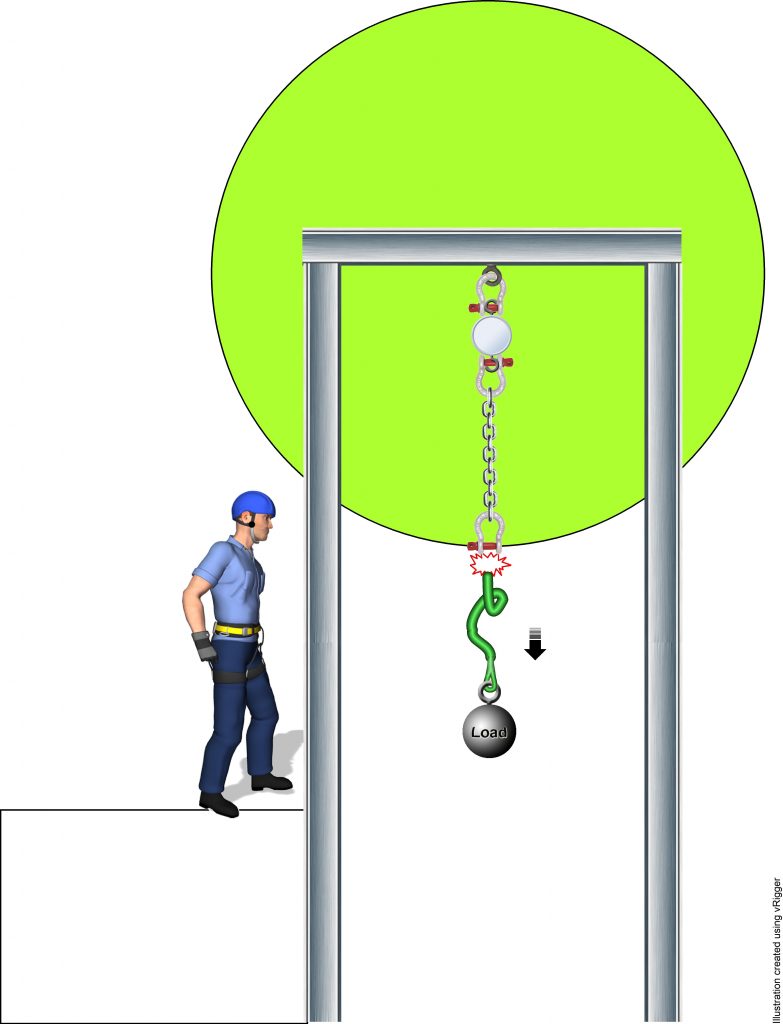

My system consisted of 1m x 12mm chain extending down from the top anchor of the drop tower. At the top was my load cell, at the bottom, a big shackle to attach the 600mm choked sling. I then raised a 100kg steel mass approx. 500mm above the shackle and hit the release mechanism.

I have always used this big chain for 2 reasons. It has practically zero stretch and it has so much mass that it should dampen any recoil. I will also note that, in all prior tests, the end of the chain has never really moved. In fact it has remained so still that I have become used to being able to set up very tight frames on my high-speed video recordings.

The accident

Well, for the first time in all of the testing I have done, the chain moved. It not only moved, it shot back up and smacked me in the face. My face was at arms length from the shackle and slightly above. An observer said the drop was perfectly vertical. Unfortunately we didn’t get the video.

My plastic-lensed glasses were smashed, their rims cut my face, and I also received a cut on the forehead from the direct impact. Nine stitches were needed. My nose and left cheek bone were also broken.

I was very lucky. I had no loss of consciousness, I remained standing, I have had no headaches, minimal pain, no eye damage, all my teeth are ok, and my eye-socket is completely in tact. The broken cheek bone will heal fine on its own.

How it happened

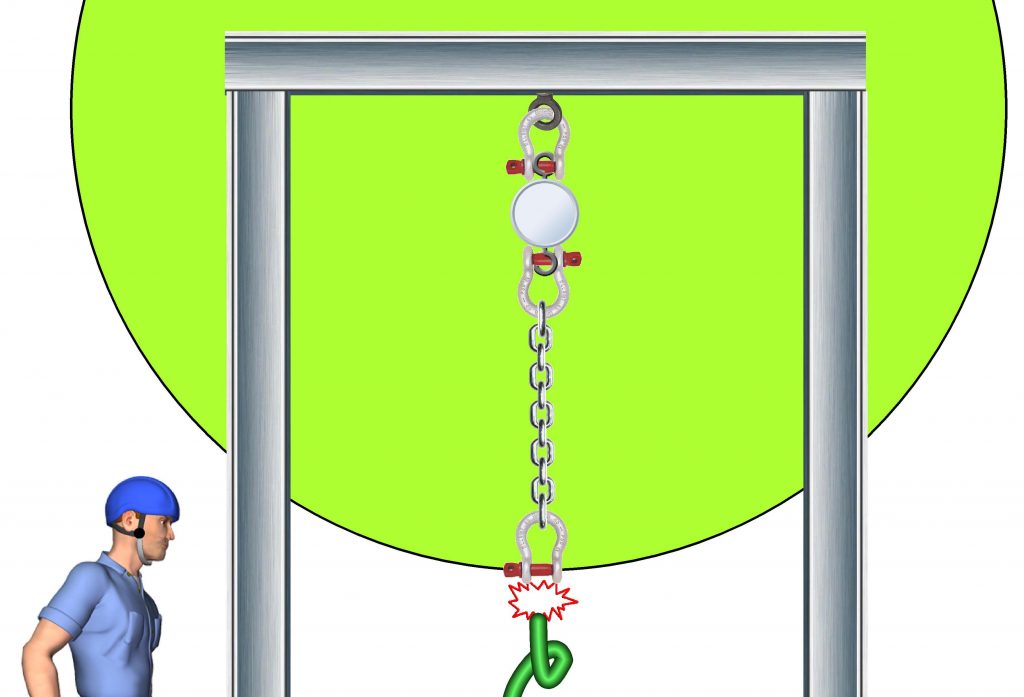

When I first set this system up in 2014 I manually pulled and moved the chain through it’s full range of possible movement and noted clearly where the spaces where it could present a hazard (represented by the green circle in the image below).

In the last six years I have used this system to conduct hundreds of drop tests and always stayed clear of this hazard zone.

Now, for these Dyneema sling tests, I decided that I needed a larger shackle for the girth hitch. I could not fit this shackle on my usual chain so I used another that was perhaps 200mm longer. I knew it was longer and that this would change the positions of things but I did not make the connection that my hazard zone was now larger. Perhaps this was due to the fact that I had never seen the chain move. Regardless, this was my key mistake.

The first drop was perfect. The second drop was when I was hit. I have always checked my system thoroughly prior to committing to the drop. There were no twists in the chain, all ropes had clear paths, there were no places anything could hang up or tangle.

So why did this drop seize the opportunity to recoil exactly in the direction of my face on only the second time it has been in the hazard zone in 6 years of testing?

The best explanation I can come up with is that as the load has been released, the chain has moved slightly away from me. Then, as the Dyneema sling was loaded, it has whipped the chain back ‘plumb’. The sling has also snapped at this point and, with a significant injection of energy, the shackle has continued on that path and up to my face.

The chain actually ended up wrapped on a part of the drop tower above my head. This suggests that my face was only just in the hazard zone and it was a glancing blow. Hence, while very concerning, my injuries have been relatively insignificant. It could have been much, much worse…

Moving on

I have been humbled by this experience. Just because we have done something a particular way many, many times without incident, that does not make it right. I know there are many others who conduct these tests in a similar fashion and they have contacted me with messages of support – and concern over their own methods.

What will I do next? Well, I’m going to design a remote release mechanism. I know there are some on the market but I hope to come up with some that is operated electrically (12V), simple, cheap, and make the design freely available to all. Of course there are some excellent commercially available solutions however these generally cost about the same as a load cell and none seem to have readily reusable electrical control options.

Once I have the remote release working I plan to get straight back into finding what happens to choked Dyneema slings.

I am so grateful for the support and encouragement I continually receive from the international roping community. I am extremely fortunate and hope to continue to make our roping world better – or at least easier to understand!

(c) Richard Delaney, RopeLab, October 2020.